Formfunktion,2025

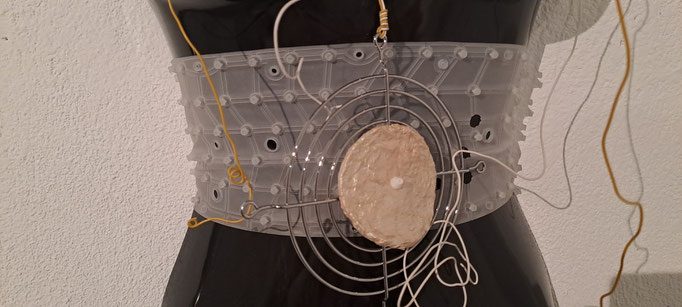

Form Function: Ansonsten I (Figure 1)

Form Function: Ansonsten II (Figure 2)

Louise & Lévi (red cable, white spheres)

Assemblage-like enclosures made of electronic waste and papier-mâché

Device components: CD player, optical reader, PC fan, silicone (keyboard parts), cables, wires. Steel cables and thimbles, body washers, papier-mâché (some lacquered), laminated castings with napkins (white spheres), chains, plastic torso.

EXCURSUS

When thinking of paper and electronic waste, one usually doesn’t associate these materials with objects worn close to the body—such as jewelry or coverings. The interior components of devices, in

particular, are perceived as elements that fundamentally contradict such associations. However, many upcycling projects by hobbyists and artists on platforms like Etsy or Pinterest now exhibit a

high aesthetic standard. Contemporary design products—such as smart jewelry—also combine electronics and aesthetics.

Papier-mâché, still often seen as a mere craft material, continues to face prejudice despite its history: on the one hand, it was used for mass production of everyday items before the advent of plastics; on the other hand, papier-mâché has been—and continues to be—used in art (cf. works by Franz West, Sonja Bäumel, or Eriko Yamazaki).

The basic idea behind these works was to make the underrepresented more visible by means of combination. Because:

Every day, we touch and operate numerous devices. Our clothes, shoes, or other coverings made of plastic touch our bodies for hours at a time—often without us knowing exactly what they’re made of, or what long-term effects this interaction with skin or airways might have.

Increasingly, PFAS (per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances—so-called "forever chemicals") are becoming a topic of concern regarding their impact on our bodies and, consequently, our health. It is likely that this focus will continue to grow in research—and that creative approaches, perspectives, and solutions will be welcomed. Today, even full-blown utopias are no longer mere fantasies; rather, many such visions have found their way into serious post-futuristic discourses and real-world practices.

All these approaches share a critical perspective—aiming at the analysis and deconstruction of established ways of thinking and social structures—though they focus on different societal aspects and draw from a variety of theoretical frameworks. In these new acts of construction, it seems we are finally beginning to learn from the past.

We actually know what needs to be done, when action is possible—and even when a situation appears hopeless, it is still, psychologically speaking, meaningful to act nonetheless.

The question of what art is allowed to do has always been present. In the discourse on sustainability in art, there is (again) a stronger focus on the use of materials. In any artistic research, alongside the material properties, sustainability aspects are likely considered, and contemporary alternatives contemplated.

Visual art has always worked with what is available or found. From objects to finished artworks, materials have been repurposed—whether primarily for aesthetic reasons or connected with an approach of retrofitting or homage (found footage). Added to this is the aspiration to work as resource-consciously as possible, as part of a holistic life concept that does not exclude artistic activity.

SPECIFICALLY

In this context, the technique of assemblage—putting something new together from found objects—is very obvious. Especially in digital times, when humanity is daily exposed to a veritable storm of

images including fake pictures (keyword: AI), manual work with different materials can also be a conscious decision for deceleration and digital detox.

In the spirit of bricolage (cf. "wild tinkering," Claude Lévi-Strauss), the artistic strategy here is a trial and error process combining salvaged old devices and casts. The focus is on a formal-aesthetic composition. Rather wild and impulsive, in the work Louise & Lévi, round paper forms were glued to cables—as a (tongue-in-cheek intellectual) reference to these two personalities.

The two torso constructions Form Function: Otherwise I & II required much thoughtful matching and precise work, with the arrangement of individual parts dictated by the body shape of the black torso, the final representational surface. This means that the language of forms was not only considered through their arrangements but also emphasized by papier-mâché casts.

This presentation surface, in its exaggerated portrayal of stereotypical female bodies, appears almost absurd when one considers the history of the charging of female bodies and their misuse as projection surfaces for all kinds of ideologies—processes that continue to this day, hardly refuted, indeed even intensified in a reactionary way. Bodies, especially those stereotypically coded as female, are still, in a seemingly self-evident way, public rather than private; they may be charged and evaluated, and as a consequence of this value system, assigned a place within hierarchically structured systems. Thus, they remain politically non-neutral and connected with attributions of power.

Repressions caused by carelessly constructed gender roles have, of course, caused much suffering—and continue to do so.

INSIDE OUT

Onto this external projection surface, the interior of the devices is applied as “jewelry,” attached in an almost polemical and forceful attempt to make visible what is usually discarded—things that are beautiful, can be beautiful, or could be perceived as beautiful.

Ultimately, there is the hope for a space of possibility—one that slows down directed attention or even evokes new ways of seeing, appreciation, or reinterpretation.

Aspects such as fashion, traditional clothing (or dress codes), uniforms, customs, or folklore naturally flow into the work—subtly or even unconsciously—through bindings or chainings, for example.

Thanks to:

© Cornelia Dorfer, 2025. All rights reserved.

info@corneliadorfer.com